bad times

The traveler explores the American Wayside, verifying the contents of a mysterious guide written by a man with whom he shares a likeness and name. Excerpts from ‘Autumn by the Wayside: A Guide to America’s Shitholes’ are italicized. Traveler commentary is written in plain text.

The east coast is lousy with old vintage shops and the old vintage shops are rife with junk. It’s not that I dislike antiques- I begrudge no one their velvet portraits and radioactive dishware. The trouble I have with the east coast is that these shops are laid out like the midwestern garage. There are no prices or descriptions, no method of organization. They are, without exception, owned by someone who vastly overestimates their memory of the store’s inventory and allows dust to settle on the books because each is wrapped in yellowed plastic bags. There may have once been a time when these stores offered the occasional gem of a find- that first edition hardback at a trade paper price but, now that we have the internet, the worth of old gray cards are no longer secret.

The saving grace of any antique shop that Shitholes suggests is that they tend to be sizable (though ‘Labyrinthine Vintage’ was a pain in and of itself). The smaller the shop, the more likely one is expected to pay for entry with snippets of their own life story and the outright spilling of the owner’s. I am disappointed, to say the least, when I arrive at ‘ANTIQUES’ and can guess, from the outside, that it is no larger than a room or two.

‘Considering the emergence of online maps and their literally-inclined search algorithms, one has to assume that the owner of ‘ANTIQUES’ (established 1943) is fairly pleased with their choice of name. We’ll see how the name fairs in the future but, for now anyway, the generation most likely to search for ‘antiques’ and to trust the first and most-capitalized result is alive and semi-mobile. The poor resultant reviews are mostly futile.

Judging by content alone, it doesn’t appear that ‘ANTIQUES’ has made any significant purchases in the last decade. Most shelves are bare and the items that remain are rotting, rusting, or generally succumbing to entropy where they rest.

The most important thing to know about ‘ANTIQUES’ is that it operates incompetently in most respects but sells no counterfeits. Assume the objects you find are legitimate and try not to dwell so long on the implications.’

The inside of ‘ANTIQUES’ is not at all larger than I suspected. It is a single square room, baking like an attic in the sun. At the center of the room is a man and his bulk is such that he fills the rectangular counter space there. The mechanics of his entry and exit into this space elude me. The man catches my eye once as I enter and he nods in greeting- the sort of curtness I can respect. Hector is asleep in the baby carrier but the man gives no signal that he notices or cares.

Much of what is on display consists of old wooden signs and rusted power tools. There are a few bins of old bottles and ceramic transformers. A chest of black and white photos. A box of comics that are no older than 1998. Several flattened board games.

I move my attention to the glass display counters and wait for the inevitable small talk but the man hardly notices me. Inside is a motely collection of electronics, some baseball cards in plastic sleeves, and a handful of political pins. I’m on the verge of leaving when one of these pins catches my attention. It says ‘Banner & Smith’ and features a small wolf in the corner where one might expect the traditional mascot of either mainstream party.

“What’s this?” I ask, and the man turns with great effort.

“What’s what?”

“What election is ‘Banner & Smith’ referring to?”

“Presidential.” He frowns. “1967.”

“That wasn’t an election year.”

His frown deepens and he hunches over. After some struggling with the glass, he pinches the metal between his fingers and stares at it, front and back.

“Misplaced.” He grunts. “Should be in the other room.”

The man nods to a curtain in the back where someone has taped an ‘No Entry’ sign.

I wait until the man loses interest in me again which is about as long as it takes me to walk over to the curtain. Peering between the frame and the cloth, I see that the next room is a near replica of this one- walls of empty shelves, a counter island at the center, and a fat man at the center of that. This near-cousin doesn’t look up when I slip inside and certainly doesn’t notice when I reel from a bout of nausea that may or may not be a result of simultaneously realizing that nothing about the new room makes sense.

There is another entrance, for instance, and several windows that appear to look out on the parking lot that I know, for a fact, is behind me. Either of the rooms on their own could easily fit into the space the walls suggest from outside but I had a look at the place from the lot and there is no way both rooms could exist in the structure I remember. This doesn’t even take into account a further curtained room on the far side of the new space.

The inventory of the new room is much like the last but a beeline for the pins tells me everything I need to know. There are several pieces from the ‘Banner & Smith’ campaign under the glass but none of the others are familiar- none of the races or slogans or candidates. ‘The Rest Are No Better Than Esther, 67’?’ ‘Trace Longfellow for PREZ?’ I’m on my way to the next curtain when I notice that the bolded brand name of a rusted chainsaw is also wrong. None of the items on the shelves are made by manufacturers I recognize.

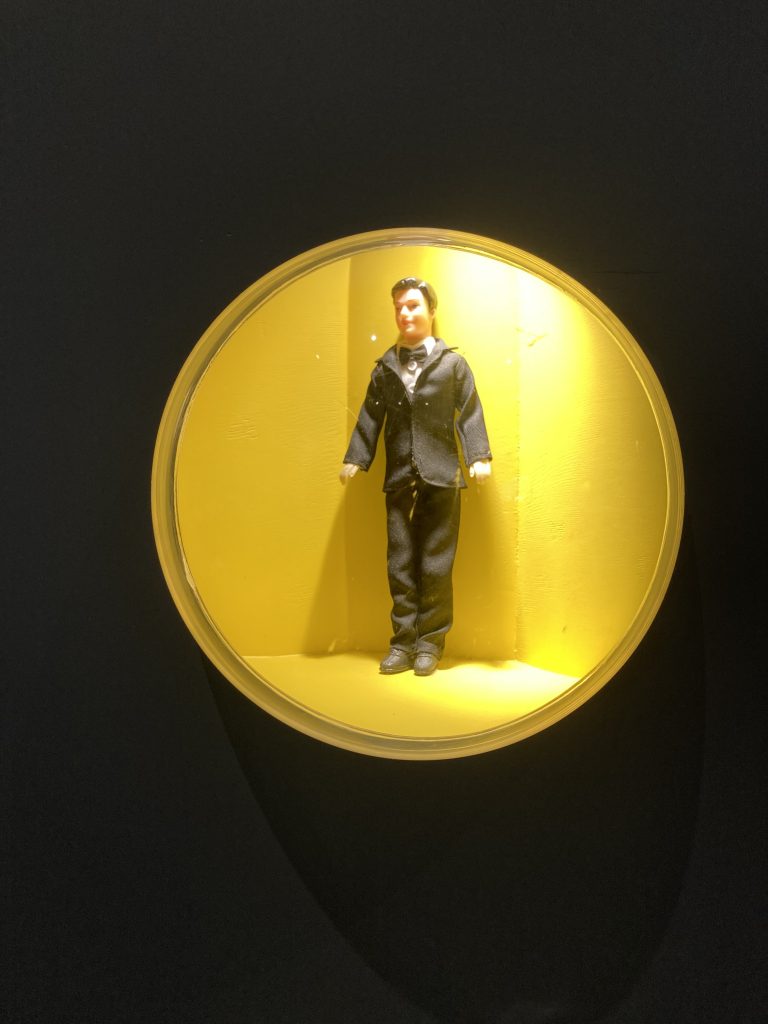

The next room is the same, but stranger. The cards in the display illustrate a game that involves naked men. The tools are twisted and made of bluish metal. There is a stray ‘McCain’ pin under the glass- likely misplaced. The rest are all variations on the same single candidate: Benjamin Bryce. ‘Benjamin: Begin Again, 1945.’ ‘Bryce is Nice, 98’’ A horse is tied up outside and the windows buzz with saturating energy. A billboard outside advertises Benjamin Bryce’s current campaign: ‘No Choice but Benjamin Bryce.’

I buy ‘Bryce is Nice’ and hurry out when the man behind the counter stares a little too long at Hector. The last curtain shivers as I pass through it, disturbed by some crossworld breeze.

A week later the metal of the pin is tarnished and red. It slips free from the clasp and is lost to the Wayside.

-traveler

‘Known colloquially as ‘The Triple Dog Dare,’ the wooden ‘Dare and Welcome’ signs of southern Georgia’s Clinch County are likely the final relic of a ghost town that has otherwise fully slipped past the veil. There are seven confirmed ‘dare’ signs that form a rough circle with a three mile radius. Within that circle are four confirmed ‘welcomes’ around the center. Dozens of unconfirmed ‘dares’ and ‘welcomes’ have been photographed in the forests nearby, most sprouting from the ground but some hanging fancifully from trees or hammered into cliffsides where the assumed viewing experience seems to be ‘freefall.’

Stories suggest that it is near impossible to reach the center of this perimeter without finding at least three ‘dare’ signs along the way. The signs, for a ‘Clinchtown,’ depict simple illustrations of gruesome injuries and death and end with the words ‘Dare you?’ The ‘welcome’ signs, arranged after the ‘dares,’ are without illustration and say ‘Welcome to Clinchtown, Population Zero.’ The backs of the signs say ‘Thank you for visiting Clinchtown.’

‘Clinchtown’ does not exist in any official capacity, state, federal, or otherwise. There is nothing overtly dangerous or suspicious about the land that these signs seem to describe. Still, people go missing in ‘Clinchtown.’ Tourists, mainly- and the more missing tourists are reported, the more a certain subsection of traveler is drawn to the area.

The Georgia General Assembly has met half a dozen times over the last century to discuss Clinchtown and the transcripts of these meetings suggest a certain knowing caginess among participants. Every instance has devolved into two distinct sides, those that are in strict opposition to the founding of an official Clinchtown and those who feel it’s best to just ‘get it over with.’

-an excerpt, Autumn by the Wayside

After a few weeks at ‘The Slim Vacancy,’ Hector and I eventually muster the energy to abandon our bed for the next lucky arrival. We don’t get far before the desolate ‘Nevadan Unemployment Center’ spills off ahead and to the west of the interstate. It’s early evening by the time we reach it- hardly dark but late enough that it doesn’t make sense to go any further. We pick a likely cubicle and, seeing the clouds gather, I unpack the tarp. Rain has already begun to fall by the time I finished the makeshift roof and slump into the cement likeness of a spinning office chair.

‘The Nevadan State Government’s manifestation of an ‘Unemployment Center’ suggests a cruel sense of humor and a severe lack of budget oversight. Though preliminary sketches of the facility are penned with such brutalism that one can’t help but assume it’s design is in jest, the project’s real world manifestation in 2006 did away with the playful artsy pretense and settled on something wholly brutal. Though someone had taken great care to model the cement likenesses of office equipment in each cubicle, the ‘Center’ was, and is, little more than a parking lot of cement outhouses baking in the sun off the interstate.

A series of PSAs aired shortly after work on ‘The Nevada Unemployment Center’ completed and these outlined the project’s simple offer: sit in these cubicles for eight hours a day and receive minimum wage. Humanitarian-based criticisms of the program are well-documented and can be perused elsewhere but most focus on that initial wave of enthusiastic participants. People from all over the state swarmed the cubicles and it soon became a thing all its own: half ironic artist retreat and legitimate tent city. When checks arrived two weeks later, a second wave of ‘employees’ appeared and demanded their turn. Violence followed, enough violence that the plan faced termination and ‘The Unemployment Center,’ a cement slab in the middle of nowhere, had to be fenced-off and guarded- a grand new tax-payer expense.

Interest in ‘The Nevada Unemployment Center’ soon waned and, criticisms aside, the oddball program may well have stabilized had it not been for the final blow. Following a tip from a small-town lawyer named Ricky Handler, all those initial ‘employees’ found they now qualified for severance and a revised unemployment package. A bill arrived somewhere at the statehouse and the guards disappeared overnight. ‘The Nevada Unemployment Center’ was abandoned, spiritually and otherwise. It remains abandoned to this day.

‘The Nevada Unemployment Center’ makes for a poor living space. It’s miles from the nearest town and provides little protection from the elements. It makes for a poor skate park- a poor background for the movers and shakers of modern social media. Nothing thrives there but snakes and tumbleweeds. It serves no real purpose but research suggests that, of all Nevada’s novelties, ‘The Unemployment Center’ will stand longer than just about anything else. If an alien shoe should step on the earth long after the human flame has been extinguished, they will know something of humanity and it will be the cubicle floor-plan of the early millennial office.’

I worked in a video shop when I was a teenager and spent the night there twice. The first time I was snowed in- I made microwave popcorn for dinner and waited out the storm. The second time was for some event- some late-night movie showing for which I never received overtime. Spending the night in a cubicle of ‘The Nevadan Unemployment Center’ reminds me of that place. Too formal to be a home. To familiar to be a business. I knew that store like the back of my hand and I didn’t mind, so much, stretching out on the floor and watching the snow fall. I didn’t mind, so much, catching glimpses of the night sky from the parking lot during that event- the crisp, midnight air. It’s like that, again, when the rain comes down onto the tarp. It’s like that when the wind flicks between the cubicles, rushing past our little shelter. Lightning flashes across the sky and I tell Hector we ought to unplug the cement computer, just in case. He blinks his cloudy eyes and finds a corner to relieve himself in.

A letter finds me two weeks later- something that hardly ever happens. It’s from Nevada and I think, for just a moment, that it might be a check. It’s a warning for trespassing: a generic cease-and-desist as though that little satisfaction might tempt me to return to that little box and to try to live out my life there.

-traveler

‘Off I-11 and not but an hour’s drive from Boulder City, Nevada there stands ‘The Slim Vacancy’ and its signage. The building itself is squat and cozy, made private via frosted glass rather than blackout shades or tinting. A smell like smoke lingers outside and low conversations are sometimes heard within. The sign stretches high above the horizon, buzzing red at dusk.

The single-page website for ‘The Slim Vacancy’ details only the exclusivity of the establishment and spares no words for the business’ purpose. Membership is based on a first come, first serve basis and is limited to just six members at a time. A neon sign indicates the current membership status and, as one might suspect, it reads ‘no vacancy’ more often than not.

Interest in ‘The Slim Vacancy’ waxes and wanes. Following its re-discovery, small crowds will sometimes gather in the lot and wait for an unlikely vacancy to occur. Nobody will stop visitors pressing their noses to the windows or their ears to the walls and nobody will response to loud knocks or calls for emergency evacuations. It’s said that the wood with which ‘The Slim Vacancy’ is constructed will stand up to fires and axe-blades, that the glass will bend but not break. It’s said that vacancies occur with no fanfare and, occasionally, with little indication of what may have been the catalyst. Of the 12 recorded vacancies, only five involved someone stepping out the door.’

If Shitholes’ author couldn’t get inside ‘The Slim Vacancy,’ I don’t hold out much hope for Hector or myself so imagine my surprise when the sign appears in the distance ahead and indicates a vacancy. I press the upper bounds of the speed limit but there’s no other traffic to speak of and no vehicles in the lot when I arrive. Just like that, my excitement becomes suspicion.

I keep Hector close as we reconnoiter the building, not entirely convinced that we won’t have to make a run for the entrance as soon as another car pulls off the interstate. Lights are on inside and, though a shadow passes by the frosted glass, it is absolutely quiet.

Several minutes tick by. I dither out front and tell myself that sometimes good things happen. Sometimes a man and his rabbit get lucky.

A squeal of tires breaks the spell. A car has swerved down the exit and aimed itself at ‘The Slim Vacancy.’ I scoop Hector from the ground, grab the bag from the bike and dash toward the building. I knock but get no answer. The door swings opens when I try the knob.

The growing engine noise is entirely blotted out by the door behind me. The inside of ‘The Slim Vacancy’ is stiflingly warm and it smells, nostalgically, of old cigarettes. A man’s head appears from a doorway. He’s leaned back in a wooden chair.

“Come on in,” he says.

‘The Slim Vacancy’ is a house, it turns out. A house with six small bedrooms. The man and two women are seated in a den, playing Graycards on an old pool table and drinking. The fridge is stocked with big-box staples and a dryer churns laundry near the back.

“Basement’s chock full’a stuff that won’t go bad,” the man, Brent, tells me, “And the owner comes around once in a while to replace things.”

Brent is a failed DJ. The women are sisters who claim to be ‘on the run.’ I ask about the Graycards and they say they found them on a shelf with several iterations of Monopoly. I ask about the owner and they all struggle to describe the person they’ve seen countless times.

“So what’s special about this place?” I ask.

“It’s free.”

The front door slams open and two more women hesitate on the threshold. I see the speeding car cooling off outside- their car. Like me, they seem thrown by the ease at which they’ve scored entry. The taller of the two steps forward.

“Is it… safe?”

I look around and shrug. “Yeah?”

“Yeah,” Brent confirms, “Sure. We’ll deal you in.”

At maximum capacity, ‘The Slim Vacancy’ seals itself off. Hannah, who has been inside for nearly a year, shows us a screen situated in the hallway closet that monitors several external cameras. On them, we see that the sign now indicates ‘no vacancy.’ The rest of the tour is simple. The three of us take bedrooms, all of which are more or less the same. Brent explains a complicated tap in one of the bathrooms and they all take turns confirming that ‘The Slim Vacancy’ is basically a comfortable place to squat as long as there’s a spot open.

“I was here a few years ago,” Brent recalls, “Vibe was different, then. A real party house. This guy, Devon, decides he’s going to make a beer run because he’s had enough of the house stuff and, just a minute after he’s gone, a guy named Arnie pulls of the road and takes his place.”

“Why’d you leave the first time?”

“Arnie was a real drag.”

The three long-term residents have already eaten but they offer us some cold pizza and a round of drinks. After a muted ‘cheers’ the six of us head off to bed. The room is comfortable and quiet. Hector falls asleep in his kennel and I doze off a little while later.

Sun filters through the frosted glass in the morning and the smell of frying bacon creeps under the door. I rest, for a while, and as soon as I consider that this is the sort of place that grows on a person- the sort of place that threatens my travel- a silhouette passes outside and a wild possessiveness clenches my chest. Leaving means giving up my spot and I’m not ready to spurn luck so soon.

Brent is tapping at the monitor when I peer out of the room. He’s got an apron on and a spatula in his hand and he looks relieved to see me.

“Would you watch this for a moment?” he asks, “I gotta flip the pork.”

A man is pacing outside. He stops and looks up- waves in the general direction of the camera. It occurs to me that he’s been inside before.

“That’s Arnie,” Brent says, back from the kitchen, “Lucky you three showed up when you did or we’d be stuck with him again.”

“I don’t plan on staying long,” I warn him, “I’ve got some work to do.”

“Tell you what, buddy. You wait Arnie out a week and I’ll cook you and your rabbit a week’s worth of breakfasts. Whatever you’re doin,’ it can’t be so urgent you didn’t keep you from spending the night on the fly.”

Hector, still clumsy with sleep, hops from the bedroom and a comfortable lethargy stirs in my chest.

“One week,” I tell him, “And if Arnie’s still here after that, it’s your tough luck.”

-traveler

Hector’s willingness to engage in travel is admirable for a blind, naked rabbit, so it’s difficult to be frustrated when I discover he’s adverse to climbing uphill for more than a few moments at a time. The check-up Hector received early in our acquaintance suggested he’s enjoying the upper-middle age of a rabbit’s lifespan. He seems healthy enough but the hardships of his life have been weathered with stoicism alone. The creature is entirely unwilling to explore the more athletic forms of endurance this late in life and a certain world-weariness may have something to do with it.

All to say that I climb Bagger Hill with Hector strapped to my chest, looking like an alien parasite in a modified baby sling. If it were a day hike I might have considered leaving him behind in the kennel, strapped to the bike and covered against wind, rain, and predators. Hector is quiet, by default, and the trailhead is well enough off the beaten path that I doubt anybody would have been in a position to steal him or to question his abandonment. Sources say the trail to ‘The Y2Kave’ takes at least two days- and that’s quickly paced. I, like Hector, have slowed down, some. I plan for three days and pack for four. Toss a rabbit’s weight on top and you have a slow hike indeed.

‘It’s common enough to find oneself nostalgic for the simpler sort of apocalypse that Y2K embodied. Imagine humanity’s unraveling, not at the hands of some insidious nuclear power or by means of plotting and coups, but as a result of simple short-sidedness in the creation of its digital calendar systems. Imagine the collective grimace- the flashing double-zeroes on screens across the globe as planes fell from the sky and microwaves silenced and the streetlamps all went out. Imagine it happened at midnight- a great wave of darkness opposite the sun, revelers frozen with their champagne. Awake, as one might be during a plague. Surprised, as one might be by an atomic blast. Alive enough to be afraid.

Alabama’s ‘Y2Kave’ is a bit of a time capsule in that regard. It is the site chosen by a group of 20-something pessimists for their final days on earth, a tribute to a night of hedonism and paranoia. ‘The Y2Kave’ is far enough off the beaten path that it has been spared defacement. Animals find the place repugnant for some reason, perhaps the residual paint fumes or the unnatural coloring of the walls.

The small cave has become an unlikely respite from the modern world- but a temporary one. The dawn of the century was, by no means, an age of absolute contentment. ‘The Y2Kave’ is the product of fear- naïve fear, perhaps, but fear just the same. Few stay for longer than a week before the place’s subtle haunting drives them away.’

Hector and I reach the cave late in the afternoon, having overshot the turnoff half a mile before catching the mistake. I’m happy to find ‘The Y2Kave’ vacant. My sense is that visitors tend to be meditative rather that rowdy but I don’t savor the possibility of having to commiserate over the state of the world. Things are obviously bad. Let me suffer alone.

Hector is asleep when I set him down in the sling. He opens an eye when I reattach his harness and closes it again once I stand. I let him rest and step into the cave.

Shitholes doesn’t mention that some amount of purposeful conservation has occurred at the site of this ancient doomsday party. Empty bottles of discontinued wine coolers have been organized along one wall. Scraps of paper have been patched together and anchored by rocks. Several other items- a frisbee, a joint, a pack of Camels, a pair of glasses- have been inventoried in the back where visitors have identified them in chalk. Two halves of a Y2K emergency pamphlet have been rolled up and pressed into a wine bottle. It reeks of late-nineties graphic design, all 3D fonts and clipart despite the dire warnings.

A controversial timeline of the party itself has been laid out on another wall, this also in chalk. The anonymous attendees of the original party seemed to have begun a mural early in the night- a visual depiction of human civilization from the beginning of time. The mural is largely western, beginning with a satirical depiction of Adam and Eve, leading into vague scenes of Egypt and possibly China, and slowing down once more for the founding of the US. To their credit, the artists had a pretty good memory of the past centuries’ American atrocities and less-satirical depictions of those events take up much of the remaining space.

The chalk timeline notes the drunken sloppiness of the painting as the timeline reaches 2000, at which point there is an unfinished sketch of the party itself followed by a couple dozen doomsday scenarios. Everything from nuclear war to alien invasion.

There is some internet chatter about a jutting rock near the end of the mural where paint has dried dark brown. Some suggest the party ended in violence, when drawn-out paranoia overcame the nihilism. The inclusion of twenty-odd cans of food and a rusted pot in the inventory suggests the potential for a longer stay- a half-hearted shelter for the early days of the end times. It doesn’t take much for humans to turn over so few resources.

I bring Hector into the cave a little later to see if he has a sense for the place. He hops here and there and he pauses briefly to lick at the bloody rock before I pull him away. After the novelty has faded he, like other animals, seems to be in favor of spending the evening outside.

It’s a clear night, and not so cold for mid-autumn. We sleep under the stars and pack up early the next morning. We make better time on the way down and are soon cast back into the troubled present, eased not by the respite itself, but for having recognized the futility of dwelling overlong in the past.

-traveler

© 2024 · Dylan Bach // Sun Logo - Jessica Hayworth