The All-Party

‘‘With an eye on Paris’ physical meter, measured in expensive lengths of platinum-iridium, the nation’s movie industry reacted to the early-eighties’ rise of the American sex comedy with a similar solution. Rather than rely on the memories of Hollywood’s aging elite (or the notoriously exaggerated descriptions provided by the then-modern teens) a group of troublesome youth were supplied a stipend, a venue, and enough booze and alcohol to throw a party as they saw fit. Two-way mirrors and cameras allowed the industry’s writers to harvest plot seeds from the all-year party (later shortened to ‘The All-Party’) and to have a reasonable defense when the prudish MPA inevitably tried to slap them with anything above an ‘R’ rating for being unrealistically gratuitous.

‘The All-Party’ was meant to be a temporary project, funded by three producers, each with a specific script in mind. When those films were inevitably lost in the late-eighties oversaturation of sex-romps, the producers prepared to disperse ‘The All-Party’ but were approached by a new batch of filmmakers, freshly arrived to try their own hand at the bloated concept. So it came to be that ‘The All-Party’ was handed down for decades, outliving many of the original participants and informing the silver screen’s understanding of what it meant to be a modern teenager for far longer than the initial one-year run. As party-goers aged out (passing the threshold even for ‘skeevy college-aged alum’) they were dragged off in their alcohol-induced slumber to be replaced by some wide-eyed transfer whose only goal in life was to comfort his crush when she’s dumped by the jock. These rookies were quietly poached from schools nationwide, usually students who had been expelled for (or dropped-out to pursue) little ‘All-Parties’ of their own.

Unfortunately for realists, ‘The All-Party’ is no platinum bar and the unit by which Hollywood measures its characters has long since warped into something altogether different. A crackdown on child endangerment has led to ‘The All-Party’s’ youngest recruits being 18. The result is that most high school melodramas are played out by full-fledged adults who tower over their lockers and struggle to act as though they’re only just learning about sex.

More importantly, ‘The All-Party’ is changed by the vacuum that maintains it, fermenting into something that is more itself than was ever initially intended. It has become such a concentrated pit of deviancy that writers now work to dilute what they witness through its mirrors in order to provide something remotely palatable to their global audience.

Participants emerge from ‘The All-Party’ with no understanding of society. They shuffle to music they no longer hear, sleep for only hours at a time, and suffer painful drug and alcohol withdrawals. Many are injured from cruel, slapstick stunts performed around the ‘The All-Party’s’ pool. Many are wracked with guilt or anxiety for having felt, for so long, that ‘The All-Party’s’ fictional parents would be arriving sooner than expected and that ‘the mess’ would need to be cleaned up before that time. Since 2007, when a drug-resistant form of gonorrhea was traced back to ‘The All-Party,’ all out-going participants are quarantined for two weeks and subject to a battery of tests upon exit. The quiet solitude of their hospitable bed is known to trigger panic attacks and therapists stand by to ease their post-party depressive episodes.

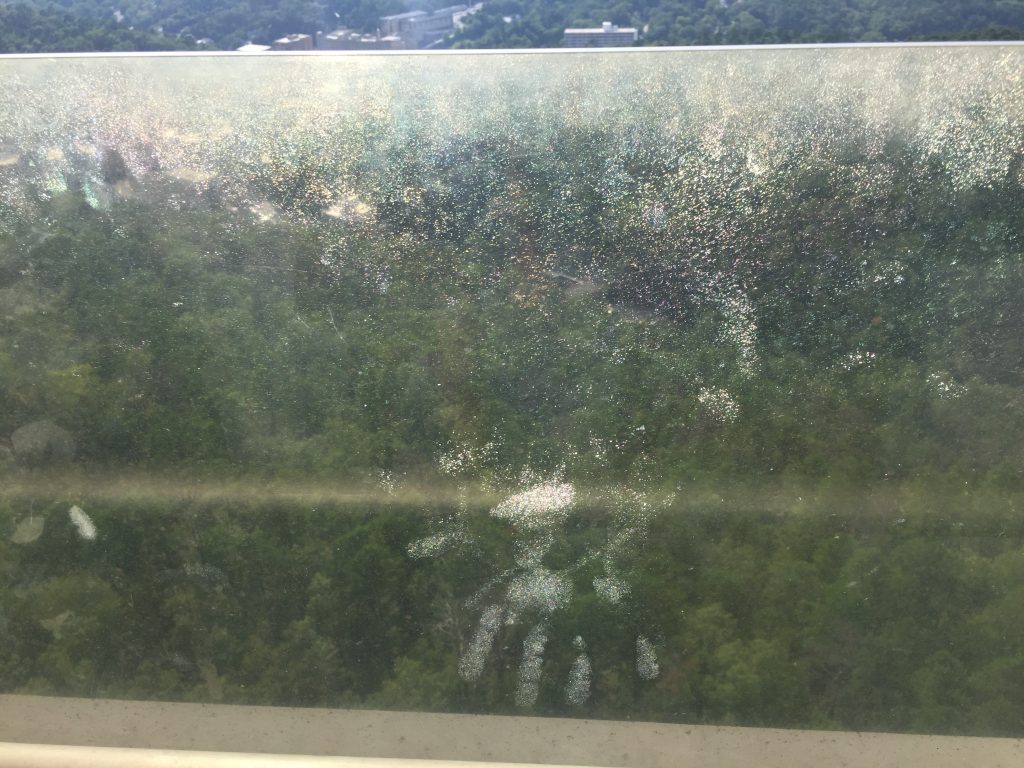

Just one of ‘The All-Party’s’ two-way mirrors are accessible to the public. Voyeurs treat ‘The All-Party Overlook’ as a sort of pilgrimage site but are often disappointed at what they find there. Those willing to describe what they saw relate a scene more evocative of science fiction or body horror than your average straight-to-streaming comedy and they grimace and shrug and wonder aloud how such a thing could even be legal.’

-an excerpt, Autumn by the Wayside