Harsh Light

‘Curated, ostensibly, by the Rangers and run by the most bored man in the American South, ‘The Sunburn Experience’ is one of many cautionary adventures presented by the Wayside. In typical Wayside fashion, ‘The Experience’ draws inspiration from older fables in that its moral is ambiguous at best but delivered with enough trauma that one can’t help but recall the wisdom it imparts, subconsciously or otherwise.’

It should be said, somewhere, that I also visit the more mainstream national and state parks as I bounce between oceans. It would be impossible not to visit them, sometimes, they being a source of clean bathrooms and comfortable benches and water fountains in landscapes otherwise parched. More than that, though, I enjoy visiting them. It’s a worthy system, run by enthusiastic people. I have annual passes just about everywhere I go: a better value for me than most.

But I stand out at these parks.

Traveling has instilled the sort of paranoia in me that makes others afraid- a paranoia that doesn’t ever really wane but that certainly intensifies in environments that I have been conditioned to find dangerous. National and state parks, having much in common with their rejected Wayside cousins, are enough to trigger that response. The response is enough to agitate others, an ancient raising of hackles. I find myself tailed, sometimes, by well-meaning staff. Mostly, I find myself alone.

All this to say that I am in my element when I step into ‘The Sunburn Experience’ because it is a Wayside destination and I am already waiting for the other shoe to drop when a blast of UV radiation strikes me in the face as I open the door. I recoil and swing around a corner where I find the restrooms and a water fountain.

“Sorry,” a man’s voice calls, “That’s been acting up. It’s… hold on. It’s off now.”

I pull my sleeve over my hand and reach around the corner at head-height. I am promptly high-fived by the owner of the voice.

“All clear, like I said.”

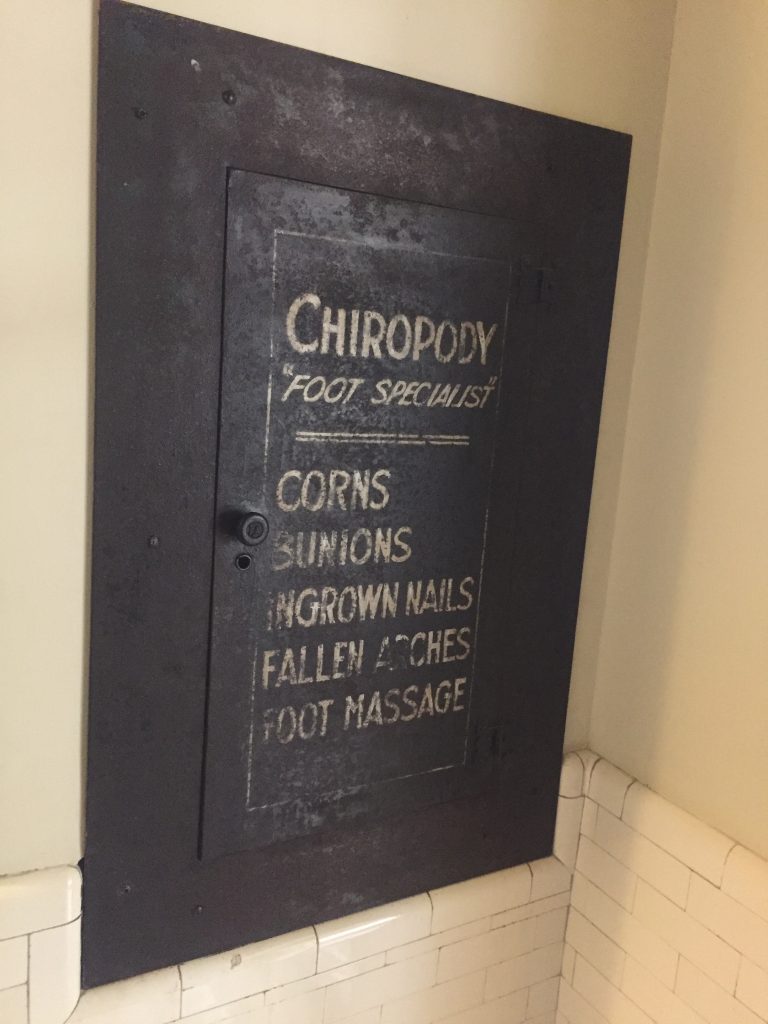

‘The Sunburn Experience’ could very well be one of the smaller state park sites, consisting mainly of a single large room with several quick exhibits. Immediately opposite the door is a counter with four hatches, each increasingly difficult to look at for all the light blazing from underneath. Other displays are less… vibrant.

“Gotcha good,” the man says.

He’s not wrong. A mirror near the glowing hatches reveals a four-inch square of raw, pink skin centered on my nose.

“What are these for if not this?” I ask, gesturing to my face.

The man presses a button on one of the hatches and it swings open again. I shield my eyes and see him hold his own hand in front of the display. He shows me his arm when it closes- tan, perhaps, but unburned.

“We’ve got a selection of sunblocks to trial over there,” he says, pointing to something that looks like a soft-serve machine, “Some sunglasses… These are just for experimenting. So, they’re for what happened to your face, only you expect it.”

“Seems dangerous.”

“Lotta lobsters walking out of here,” he shrugs, “But they know better next time.”

The man looks about the room, betraying a certain pride that makes me like him a little more. I follow as he walks to another wall.

“Over here we’ve got our timeline- folks who start with this normally don’t get caught by the box-light. That’s a fresh burn- still hot.”

The timeline consists of several human backs embedded in the display, ranging from bright red to dry and peeling. The man presses his hand into the first and we watch the shape of it slowly fade from normal, to pinkish, and finally back to crimson.

“Try it out.”

I begin to spell my name with my finger and the display shifts uncomfortably.

“Sheesh, man,” he says, “Take it easy on the interns.”

I recoil and he laughs in a way that makes it difficult to tell if he’s being serious. He leads me past the timeline, casually pulling a strip of peeled skin from the last display, and toward a glass cage, the contents of which are a relative model of the desert that surrounds us.

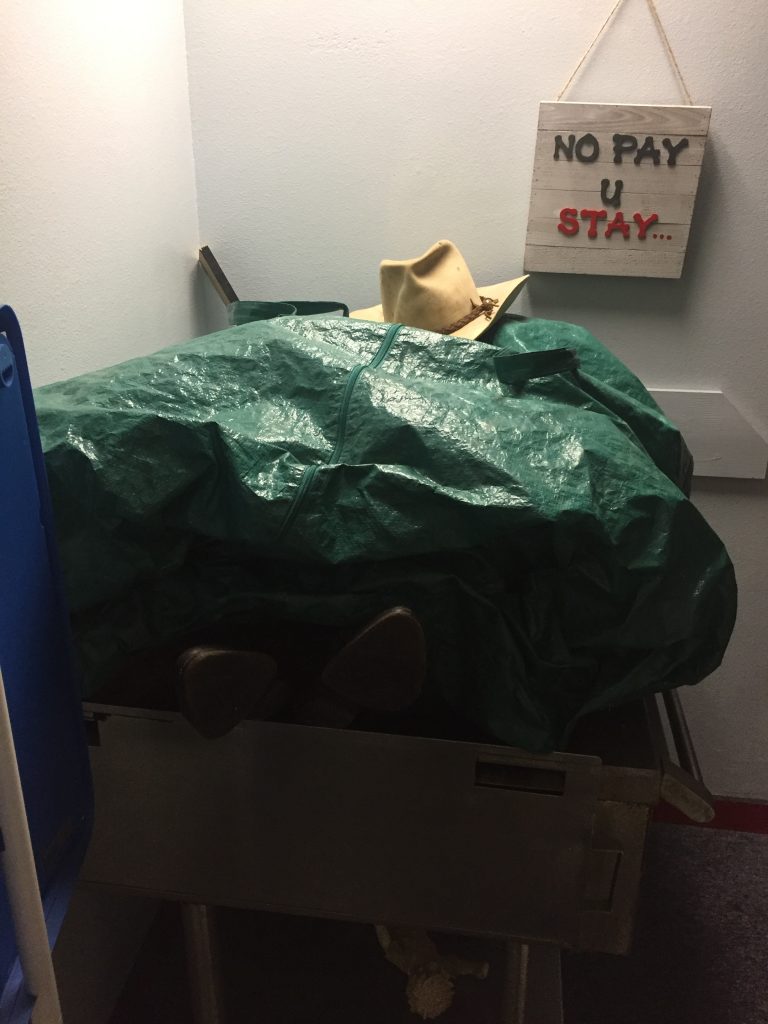

Inside is a single, shaved rabbit, its skin motley with tanning. Above it are a variety of filters and, above those, an impressively large, thankfully-inactive lamp.

“Seems up your alley based on your performance back there,” he says, “Dial in a pattern on the display and get to toasting.”

The man taps through several animal prints and holds down a large, red button. Blinding light fills the little cage for a second or two before he lets off. The rabbit has become faintly tiger-striped and its bowl of celery has wilted.

“Hector!” the man calls through the glass, “Looking ferocious!”

The rabbits eyes are pale white. It picks lethargically at the celery.

‘The Sunburn Experience’ has no real security to speak of, but, upon shimmying open the door in the dead of night, I do forget about the malfunctioning counter and stumble blindly through the dark for several minutes before my sight returns.

Hector is a hefty, leather lump: naturally calm or tormented past a point of traumatic serenity. I spend exactly five minutes trying to convince him to wander off into the brush before admitting to myself that I would survive in the desert longer than the broken creature at my feet. He goes back into a comfortable kennel and the kennel goes on the back of the bike, insulated against wind to the best of my ability. I’ll look up shelters when I’m back in cell range.

‘The Sunburn Experience’ burns to the ground, not so strange considering the high intensity bulbs and the faulty displays. The story is picked up in the local papers and, by then, Hector and I are miles away.

-Traveler